Materials for the Real Easter Egg

in UncategorizedSample Bulletin Announcement

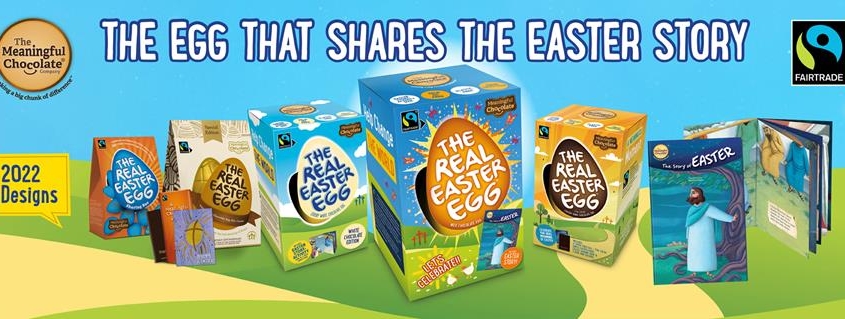

An Easter egg that is really good news!

The Real Easter Egg is a great way to share good news with people close to home and far away. Each egg comes with a copy of the Easter story, telling the Good News of Jesus’ resurrection. And because the chocolate egg is Fairtrade, cocoa farmers benefit, too, receiving the Fairtrade minimum price for their cocoa, and a premium that helps them improve life for their families and communities.

Large eggs come in milk and dark chocolate, and there are also fun packs – egg cartons with six, smaller eggs. Prices are [X] for milk chocolate eggs, [Y] for fun packs, and [Z] for dark chocolate eggs. To order, contact [A]. The eggs contain no palm oil, and the packaging is plastic free.

NB: We have left out the prices, as these will vary depending on whether eggs are purchased singly or in cases, and on whether the orders are large enough to qualify for free delivery. For a church that purchases in cases and in sufficient quantity to qualify for free delivery, prices would be:

£4.50 for milk chocolate eggs, £5.00 for fun packs, £5.50 for dark chocolate eggs

There is also a sharing box of 30 eggs for £30 – great for Easter egg hunts and/or handing out at services!

A Prayer to use with the eggs

Heavenly Father,

We thank you that through Jesus’ resurrection

We are given the hope of new life.

We pray that the story told through these eggs

Will be a source of life for all who receive them.

We pray for the farmers

Who produced the cocoa and sugar for these eggs,

Thanking you that through Fairtrade

They are able to benefit from the fruits of their labours.

And we pray for the coming of your Kingdom

Here and throughout the world,

In Jesus’ name.

Amen

“How then shall we live?”

in Fair Trade Reflections, UncategorizedAnd the crowds asked him, “What then should we do?”

In reply he said to them, “Whoever has two coats must share with anyone who has none; and whoever has food must do likewise.”

Even tax collectors came to be baptized, and they asked him, “Teacher, what should we do?”

He said to them, “Collect no more than the amount prescribed for you.”

Soldiers also asked him, “And we, what should we do?” He said to them, “Do not extort money from anyone by threats or false accusation, and be satisfied with your wages.”

As the people were filled with expectation, and all were questioning in their hearts concerning John, whether he might be the Messiah, John answered all of them by saying, “I baptize you with water; but one who is more powerful than I is coming; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.”

So, with many other exhortations, he proclaimed the good news to the people. Luke 3:10-18

A society ill at ease, waiting for a saviour to redeem it, encounters the last of the prophets, coming from the wilderness. He preaches repentance and judgement, his extreme lifestyle giving credibility to his powerful words. Moved, the crowds ask him for guidance. “What then should we do?”

John’s response is a very practical call to generosity, honesty and justice. Those who have more than they need are to share with those who have less. Tax collectors are to be honest – and to avoid the practice of gathering more than is owed so that they can keep some themselves. Soldiers are likewise to be satisfied with their wages and not to abuse their power for personal gain.

His answers, which echo prophetic calls to justice throughout the Old Testament, fill the people with expectation – can this be the Messiah?

No, responds John: he is the precursor. He baptises with water but will be followed by one greater than he, who will baptise with the Holy Spirit and fire.

There’s an interesting symmetry between this passage and Acts 2, in which after the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, Peter preaches to the assembled crowds. Filled with the Holy Spirit, the apostle shares the message that the Jesus who was recently crucified has been raised from the dead and is Lord. Once again, the crowds are cut to the quick and cry out “What shall we do?”

Peter’s response is a spiritual one: “Repent and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is for you and for your children and for all who are far off, everyone whom the Lord our God calls to himself.”

But does that spiritual response mean that the old practical call is no longer important? Far from it. Rather, the disciples’ calling has been intensified in a way that flows from the transformation that God’s grace is working in them. “All who believed were together and had all things in common, and they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need. And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they received their food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved.”

The new community is one of the deepest contentment, thanksgiving, generosity and justice.

What of us, today? On the whole, our society – and often our lives and our churches – resemble the confusion of people coming to John in the wilderness more than the transformed community of the apostles. Whether it’s money, vaccines, food or access to education, our societies are riven with vast inequalities – and often a resistance to sharing. Corruption and violence make some wealthier, and others poorer. We see these things all around us … and all too often, we know them in our own hearts.

And so we, like the inhabitants of the Holy Land at the time of Jesus, need to hear both John the Baptist’s and Peter’s messages. At the very least, John tells us, share if you have more than you need, be content with what you’re owed, and don’t seek to take from others to enrich yourself. As a sign of your transformed life, Peter tells us, go even further – treat all goods as no longer ‘yours’ but for the good of all, pray constantly, praise God and be thankful.

How does this relate to Fair Trade?

In many ways, Fair Trade speaks to some of John’s commandments. When those of us who can buy Fair Trade products to meet our needs, we turn our back on the exploitation practiced in so much mass production and turn towards a model that involves cooperation, care for the environment, safe working conditions and better pay. In doing so, we may find ourselves having to buy less. Fair Trade goods don’t necessarily cost more – and are often similar to the costs of other brands. But they are also rarely absurdly cheap, unlike some of the goods we see in shops, because the Fair Trade price costs in sustainability for people and planet. When we buy Fair Trade we accept that – and we don’t try to get more than we should by shortchanging our neighbours or the earth.

But Fair Trade doesn’t just help us avoid exploitation. Ideally, it points us towards a transformed life in which all people are valued as precious, made in God’s image, and goods are shared so that no one is in need. Ideally, it reminds us of our mutual dependence on God, and helps us to see how right relationships – with God, the earth and each other – are more important than acquisitions … and the needs of our neighbours are more important than our ‘wants’. Ideally, it points us towards a transformed community.

Pray that God may guide us, so that we make choices that foster right relationships. Pray that God will give us the grace to live out our love of God and neighbour – following the greatest of commandments.

Picture: John the Baptist Preaching, John the Baptist Basilica in Berlin. By Beek100 – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3100267

Responding to the cuts in UK aid

in UncategorizedTable of contents

What has been the recent level of the aid budget? And how and when was it cut?

In 2015, the UK Government passed legislation committing the country to allocating 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) to aid. Reaching 0.7% of Gross National Product (GNP) had been a target set by a UN resolution in 1970; as of 2019, five countries had achieved it: Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and the UK, with Germany and the Netherlands the next closest, at 0.61% and 0.59% respectively.(1)

Committing to aid at this level has made the UK a leader in development. It has been the third largest donor (behind the US and Germany) in absolute terms. And, while there have been conflicts about the nature of certain aid projects, the UK has been responsible for significant achievements through both its bilateral aid and the donations it has made through multilateral institutions. Tearfund recently noted:

“More than 11.3 million children have been given access to education … UK aid has also provided vaccinations to more than 67 million children in the last five years alone, protecting them against preventable diseases. The money has also helped 12 million people have access to clean, sustainable energy … Life-saving support and assistance has also been given to communities devastated by natural disasters, such as hurricanes and floods.”

Because the amount of aid is linked to GNI, it would inevitably have fallen given the contracting in the UK economy in 2020. But in addition, in November of last year the UK Government announced that, in response to the fiscal issues caused by the Coronavirus pandemic, it would “temporarily” – though without any definition of timescales – reduce the aid budget further, by moving from the legally binding commitment of 0.7% of GNI to 0.5%. Writing in the Financial Times, the Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab, expressed “regret” for the decision, but did not state when the target would be reactivated, commenting simply that it would be “as soon as the fiscal situation allows.” He noted that the UK was still one of the largest donors in the G7 in terms of percentage of GNI and that reaching the 0.7% target was something done only relatively recently.

What concerns were raised at the time?

There were widespread concerns about the fact that this was the breaking of a promise, a derogation from a legal obligation and from a manifesto commitment, and that the cuts were coming at a time when the aid in question was desperately by countries and communities that had themselves been battered by the pandemic.

The Archbishop of Canterbury wrote: “The foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, insists we are still giving lots. Perhaps, but to those whose projects are cut off — and to our reputation as trustworthy — that is not the point.” He cited a host of reasons for maintaining foreign aid. Some were moral, focused on the importance of keeping promises to the poorest and alleviating suffering. Some were political, relating to UK aid’s contribution to a rules-based order. And some were self-interested: at a time where Britain is embarking on a renegotiation of its global relationships, it needs stability for trade and development, recognition as a reliable partner, and the ability to tackle with others the global issues that face us all.

The Sustainable Development Minister resigned in protest, writing:

“I believe it is fundamentally wrong to abandon our commitment to spend 0.7% of gross national income on development. This promise should be kept in the tough times as well as the good. Given the link between our development spend and the health of our economy. the economic downturn has already led to significant cuts this year and I do not believe we should reduce our support further at a time of unprecedented global crises…”

“Our support and leadership on development,” she continued, “has saved and changed millions of lives. It has also been firmly in our national interest as we tackle global issues, such as the pandemic, climate change and conflict. Cutting UK aid risks undermining your efforts to promote a Global Britain and will diminish our power to influence other nations to do what is right. I cannot support or defend this decision.”

How are the cuts affecting countries suffering from conflict and hunger

Four months in, what is the impact of the cuts on some of the countries with the greatest humanitarian needs? We can take as examples two countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo and Yemen.

The needs in the Democratic Republic of Congo have continued to escalate over the past year. A recent UN report stated that one third of the population – 27 million people – was suffering from high acute food insecurity with 7 million of those suffering from emergency levels of hunger. The causes include both “the slump in DRC’s economy and the socio-economic impact of COVID-19” and conflict, especially in the eastern provinces of Ituri, North and South Kivu and Tanganyika, and the central region of the Kasais.

Such numbers are almost too big to grasp – but each of those millions of people is precious, made in the image and likeness of God. Some of them are young children, for whom malnutrition in the early years may lead to stunting, hindering their ability to reach their full potential.

In the long term, development and security are key. In the short term, getting assistance – especially to those areas where there are large numbers of people displaced by conflict, with no source of food – is vital. As we were writing, MSF indicated that there were 26,000 displaced people living in huts around Boga; news came through of 21,000 displaced by an outbreak of violence in Kasai; colleagues in other areas speak of thousands of displaced families for whom they are trying to provide shelter, food, medical treatment, psycho-social and spiritual care.

Against this background, it has been rumoured that the UK aid budget for the DRC will be cut by 60% this year, from roughly £180 million to £72 million. Such cuts would be in line with what the One Campaign’s analysis suggested would be the consequence of the overall reduction in aid.

Nineteen agencies working in the country have united to ask the Government to reconsider, stating: “As the second largest aid provider to the DRC, any cut to the UK aid budget will be a hammer blow to a country now facing multiple crises. But if the reports of a 60 percent cut are to be believed, this could mean entire communities lose access to life-saving humanitarian aid. The human cost of this decision would be devastating. We implore the UK Government to rethink this disastrous decision” The Guardian quotes Benjamin Viénot, country director for Action Against Hunger, as saying: “I have never seen such malnutrition need as here. We are treating children with complications such as diarrhoea, malaria or eye disease. They cannot eat by themselves so they need therapeutic milk or sometimes a tube from their mouth to their stomach. It is very clear what will happen if these cuts happen. We will only have 80 of the planned 210 health centres. That is 50,000 children’s lives not saved. I have a very great respect for the Foreign Office, but I am not playing games about the consequences of these cuts.”

Yemen

The ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen is one of the world’s most severe. This past week, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock delivered a briefing to the Security Council which was clear about his frustration with the situation – and the relative lack of international response.

“The situation in Yemen – already the world’s largest humanitarian crisis,” he began, “is still getting even worse.” COVID had reappeared; health workers were getting ill; hospitals lacked space and supplies to treat people who came to them; vaccines had arrived, thanks to COVAX, but only 360,000 doses, far from sufficient to contain the latest wave.

“This second wave,” he added, ” is coming at a time when large-scale famine is still bearing down on the country. Tens of thousands of people are already starving to death, with another 5 million just a step behind them.”

“To stop this unfolding catastrophe,” he stated, “we urgently need action on the five points I brief you on every month: protection of civilians; humanitarian access; funding; support for the economy; and progress towards peace.”

Some of these issues are primarily under the control of the warring parties in the country and region. But, he added:

“On funding for the aid operation … more money for the UN response plan is the fastest, most efficient way to save millions of lives. Right now, agencies are able to help only about 9 million people a month. That’s down from nearly 14 million a year ago, and that’s essentially because of the funding cuts. As you know, on 1 March, we got promises of $1.7 billion at the pledging conference. That is, as you know, less than half of what we need. Of the pledges that were made, about half have been paid. So what that means is that today, the response plan is less than 25 per cent funded. So again, as I have said many times before, without more funding, millions of Yemenis will be staring down a death sentence before the year reaches its close”

Part of that shortfall came because at the March pledging conference, the UK announced it was cutting its aid to Yemen by 60%.

The decision to make cuts to Yemen’s aid has occasioned widespread condemnation. Andrew Mitchell, MP, a former Conservative Secretary of State for DfID, said it was “unconscionable” that “the fifth richest country in the world is cutting support by more than half to one of the poorest countries in the world during a global pandemic.” Calling it a “harbinger of terrible cuts to come,” he added “Everyone in this house knows that the cut to the 0.7 is not a result of tough choices, it is a strategic mistake with deadly consequences.” On Tuesday, 20 April, the International Development Select Committee has scheduled a hearing to investigate the matter. An open letter from 101 charities commented: “”History will not judge this nation kindly if the government chooses to step away from the people in Yemen and thus destroy the UK’s global reputation as a country that steps up to help those most in need”

How can we pray?

Tearfund suggests the following prayer points on aid:

- Pray that the government will have compassion on people living in poverty around the world and restore spending to previous levels quickly.

- Ask for the UK government to look for opportunities to reverse the decision, and be transparent about how the remaining aid budget will be spent and what will be cut.

- Keep in your prayers people living in poverty for whom this decision will impact the most. Pray for their protection, and for help to reach them so they are able to overcome poverty.

In addition to praying generally, you might wish to pray quite specifically for your MP, and for a particular country. If you’re interested in praying for the countries we’ve mentioned, the Congo Church Association suggests prayers:

- ·for the authorities to bring an end to this cycle of violence and atrocities, impacting every sphere of life

- for peace so that people may return home and rebuild their lives

- for church leaders, pastors, lay workers and Mothers’ Union members as they lead churches and reach out to their communities with compassion, care and the Good News of Jesus Christ.

- for provision of care, food, shelter, and God’s blessing on the churches’ response

What can we do?

For the weekend of 6 June:

Ring your MP or write them to express your support for an amendment which would reinstate the 0.7% commitment.

You can use online forms from the Joint Public Issues Team or Global Justice Now, or, use this blogpost and the CTBI briefing to compose your own letter (something you write yourself is always the most effective). And we’d be really grateful if you could let us know if you do it.

(1) Actual percentages: Luxembourg (1.03%) Norway (1.03%), Sweden (0.96%), Denmark (0.72%) and the UK (0.7%). All data from OECD: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/TAB01e.xls

Make COP26 Count!

in UncategorizedMake COP26 Count programme – April 2021

The UN Climate talks this November in Glasgow, also known as the Conference of Parties or COP26 will bring together international leaders to tackle climate change.

It’s a crucial meeting: countries have been invited to present updated national plans to cut emissions and to agree the last portions of the rulebook for the groundbreaking Paris Agreement, signed in 2015. Scientists have told us that we need ambitious and immediate action to meet the challenge the world faces. As part of the church’s mission, we need to make it clear that the time to act decisively on this issue is right now. We are therefore inviting churches to become part of a programme designed to help them take manageable and appropriate action themselves and to build constructive relationships for climate action.

This isn’t about one-size-fits-all approaches. Make COP26 Count is designed to help you work out what your church should do – and to equip you to carry out your plans. It’s flexible to allow for different church situations and preferences for action. The aim is to provide a supportive structure to make whatever action you choose focused and doable.

The programme understands action to be holistic – practical action is rooted in shared faith motivation. It will offer input from partners in other countries, bringing global perspectives to deepen our understanding of the urgency the world faces. The programme also acknowledges the political influence of the UK as hosts of COP26, which makes this year a particularly strategic time to mobilise our churches to action.

A cohort of 30 churches began the programme in January. They have found the programme and the monthly calls invaluable in moving their church to action. The success of this first group has spurred us to organise a second cohort.

This cohort is being coordinated by Hope for the Future, Christians for Creation Care (an east London and Essex network) and Christian Concern for One World (an Oxford network).

The programme combines the principles of –

Connection

Building relationships across participating churches, with global church partners, and within your church. These connections are a source of information and encouragement, facilitated by monthly Zoom calls, and groups on Microsoft Teams and WhatsApp.

Inspiration

The regular Zoom calls will often include guest speakers from churches in the global south. By learning more about how climate is affecting their communities, we will develop a deeper understanding of the urgent need for action.

Commitment

Churches are asked to identify which action they will take and focus on meeting these goals within the set time frame. Hope for the Future, Christian Creation Care and Christian Concern for One World bring practical support, training and access to expertise to make this possible.

What will the programme look like?

Churches will be asked to name two lead participants who will report back to their church. Participants will:

- Commit to the regular calls

- Plan and undertake a particular action with their church

- Share in the exchanges of information and inspiration among participants

Calls

The centrepiece of the programme will be the regular Zoom calls, when we’ll have a chance to be inspired. There will also be additional sessions which focus on how to build constructive relationships with politicians in order to create change. These will be run by Hope for the Future, who are a leading agency in this field.

Information about regular guests to the Zoom calls will be given closer to the time.

| Regular Zoom Calls

Mondays, 7.30pm |

Additional Sessions and information

Main months of action are May – July |

|

| April | 26th – Introduction | Three weekly schedule |

| May | 17th | Monday 24 May: Session 1 on creating constructive relationships with politicians. Attend either 11am or 7.30pm. |

| Jun | 7th | Monday 14 June: Second political session. Attend either 11am or 4.30pm |

| June | 28th | |

| July | 19th | |

| Aug | Break | |

| Sep | 13th | Close and joint celebration with first cohort |

| Oct | ||

| Nov | COP26 |

What sort of actions could my church take?

Each church will choose actions that are relevant and appropriate for their particular congregation. Some churches are choosing to become an Ecochurch; some are focussing on hosting a Climate Sunday event; some are using energy footprint tools to completing an Energy Audit of their church and create a plan to reduce emissions to Net Zero by 2030; others are hosting an energy switch day event (moving energy providers to renewable energy); all are encouraged to meet their MP to discuss COP26.

How to join

As a first step, we are asking all churches to identify a primary and secondary contact, and get agreement from their church leadership to participate in this programme. Hope for the Future has learned that securing the support of the church leadership at the outset is crucial for any successful action. Please contact us for a link to the application.

I’m an additional named contact, what’s my role?

Please feel free to participate as fully as you can in the programme – everything is as open to you as it is the lead contact. However, we would like to keep attendance at monthly calls as consistent as we can, so if you don’t want to commit to the calls, you can speak with your lead contact. Other than this, it is very much up to individual churches to arrange how you want to organise your participation in the programme and divide up steps you need to take to act together as a church.

How will this programme have an impact – especially politically?

You will find out far more about this at the political training sessions in May and June. But broadly speaking, meeting with MPs is the best way to get them to take action (MPs largely ignore campaign emails). Hope for the Future has gained lots of experience in facilitating MP meetings to secure concrete action (some of our best work has been with Conservative MP Alex Chalk who then introduced the Net Zero legislation into Parliament – we’ll talk through some other examples in the training too).

MPs are often keen to engage with churches because they represent a wider group than just an individual. They are also not necessarily associated with environmental concerns (unlike local campaigning groups) so this gives churches additional influence in this area.

Can this be taken further?

Of course! To some extent, how far the programme goes is dependent on participant churches. There is opportunity and welcome of action taken as a cohort rather than by individual churches. Suggestions to date from individuals on the programme: engaging with the press, contributing collectively to a new or already existing campaign. It may be that some or all of the participant churches join in with other planned events.

Search your heart and choices – individual

in UncategorizedOne of the glories of the Christian faith is that our awareness of God’s love and forgiveness means that we can look at ourselves honestly – seeing the gifts that God has given us and knowing that when we find things that need mending, we can bring them to the God who forgives us, heals us, and sustains us on new paths.

In this section, we take time to know ourselves – the way we feel and think, the gifts of expertise and experience that we have, the reality of our lifestyle impacts, and the choices behind them – so that we can offer our whole selves to God for transformation.

The Ignatian tradition of spirituality makes use of something called the ‘Examen’ – a way of reflecting on daily life to see where one has encountered God and to gain a sense of God’s direction. It is a daily practice with five basic steps (summary taken from the Ignatian spirituality website)

1. Become aware of God’s presence.

2. Review the day with gratitude.

3. Pay attention to your emotions.

4. Choose one feature of the day and pray from it.

5. Look toward tomorrow.

The first two steps on the Journey of Hope and Love reflect the first two steps of the Examen. Now we come to paying attention to our emotions … the way we think … and what we are actually doing.

The process below is something that you might want to do in a single session, or to spread out over time (do try to do steps 1 and 2 together). Whatever you do, don’t rush it. These are important questions, and you need time for them.

Step 1: What gives me joy or hope? What breaks my heart?

What things about our world – creation as God’s gift and the current situation in which we find ourselves – make me rejoice or feel hopeful? What are the things that break my heart?

You might want to take the time to write down a list – with space for adding things as you continue the journey. Look at the list. What does it tell you about yourself? What is most clearly moving you? Is it the experience of beauty or destruction? A new development – positive or negative – in knowledge? Something relating to your faith? Something about other relationships?

What, when you reflect on it, have you not mentioned that you wish you had?

For some people, this may be a challenging exercise, as they are moved by what the Ecological Examen calls “the splendor and suffering” of all that is around us. Try to make sure that you find occasions for joy and hope, even if they are small ones. If you feel overwhelmed, stop, and lay that before God.

You might also find helpful the introduction to the Anvil edition on Hope – which speaks of hope being something that comes through suffering and perseverance.

At the end, lay your emotions before God as an offering of yourself, thanking God for creating and loving you and all around you, and asking for the grace to be shown how God is calling you through your emotions, experience and knowledge.

Step 2: How do I feel God calling me through both joy/hope and grief?

What do I feel God saying to me as I lay my emotions out in prayer? When do I feel drawn closer to God? When do I feel a sense of distance?

Time to Wonder and Respond – Churches

in UncategorizedOur church buildings are a glorious gift … but the whole of Creation is also a ‘church’, revealing God’s glory and presence. How can you, as a church community, come to be ‘at home’ together in creation, sharing together in its joys and sorrows and growing in a desire to care for it?

Worshipping in buildings that are designed to give glory to God is a joy. But it can keep us firmly focused on what goes on ‘inside’.

As a congregation, can you take opportunities to share together in experiencing the wider creation?

A first step for people who like to start with reflection …

You might want to start with something simple in a time of prayer – perhaps

- asking people to share pictures of natural beauty that inspire them … in our virtual times, you could perhaps share them on screen during worship, or on your website. When we’re in churches, you could perhaps create an installation

- asking people to bring to worship (online or in the church) something beautiful … a pebble, a fallen leaf, a fallen twig. Give them time to contemplate it during the service – really to look at it in all its intricacy – and ask them to share their reflections. What do they notice? What does it say to them about God? About our relationship with the wider creation?

Give people space to express a range of emotions. Some people will focus on beauty and joy … some may focus on pain and lament, as they think about creation under threat. Throughout the journey, thanksgiving and pain may be tightly bound. The key is to remember that both acknowledge, in their different ways, the marvel of creation, and the imperative to care for it.

A first step for people who like to start with knowledge

Do you know what’s in your church, churchyard, and local community?

Some churches have found it really interesting to start their journey of creation care just by finding out what’s around them. You could do a wildlife survey – even a church without a churchyard will have wildlife around it … bugs on the walls, birds flying onto the roof, mosses growing in cracks. You could spend some time beforehand finding out about what’s in your area generally, and ask people to identify what they can spot. People can do that individually as they walk around the churchyard, or in family groups. And once we can meet again together, you might want to have a morning for everyone to take a different part of the church/surrounding area to map and compare notes!

As you do the mapping, why not also bring each being you find before God in prayer – giving thanks for the marvel of their life and praying for them as part of the web of life.

A first step for people who like to begin with action

Could you enlist people to take on a role caring for some part of the area around your church? Whether that’s building up a planter in an urban area or cultivating local wildflowers in a country churchyard, engaging with the natural world on your doorstep is a great way of building appreciation of it. Caring for God’s Acre has helpful suggestions.

You might find it helpful to have the people who are involved in this care providing regular updates for your church bulletin … a kind of natural diary of ‘what’s on’ in your surroundings!

Going Deeper

In prayer and reflection…

Consider holding services or prayer walks outdoors … or maybe even establishing an ‘outdoor’ or ‘forest church’ congregation. You might want to explore the resources for outdoor worship put together by Leeds Church of England Diocese.

Consider writing your own song of praise relating to local wildlife. Read the New Zealand and African prayers asking all creation to bless the Lord (found in session 4 of And it was good) – what would you include in yours?

In knowledge …

Why not invite a local conservationist to talk at your church about the wildlife around you? Take a look at the map for contact details for local nature reserves and the Community Action Groups.

Consider, too, creating some information sheets about the wildlife you’ve found … useful for anyone visiting the church.

Ground everything in prayer

in Uncategorized“First of all, every time you begin a good work, you must pray to Christ most earnestly to bring it to perfection.” Rule of St Benedict, Prologue v 4

Wherever you are in your journey of ‘ecological conversion’, prayer is at the centre. Prayer can help us hear God, appreciate God’s goodness, feel God’s prompting as we seek to respond.

Ask Christ to show you the right way of prayer for you

- Some people love to use language to pray to God. Others will be like Julian of Norwich, who in contemplating a simple object, a hazelnut, had a profound revelation of God’s presence. Some people need to be still; others find they pray best when walking across a field or park or hilltop. There’s no right or wrong. Some ideas:

- Formal prayers

- Prayer walks

- Contemplation of objects

- Alone or with others

-

Setting routines …

Many people find it helpful to have a set time of prayer each day. Some options

- Arrow Prayers

Contact Christian Concern for One World

The Rectory

Church End

Blewbury

OX11 9QH

Tel: 07493 377580

Email: maranda@ccow.org.uk